I’ve been thinking a lot about distraction recently. And as tends to happen whenever I think about anything for longer than five minutes*, my thoughts begin to wander etymologically. The etymology of distraction isn’t overwhelming, but the origins of ‘focus’, distraction’s elusive sister, are quite lovely.

Distract comes from the Latin dis (away) + trahere (to draw or to drag). When we are distracted, we are drawn away from our focus. So far, so intuitive. But focus? Well in Latin, focus was a domestic hearth. This seems immediately appealing, with my mind instantly making connections about the hearth being the focus of the home (and the 20th Century struggle between the fire and the television to be the focus in our living spaces, which remains largely unresolved despite some deeply uneasy attempts at neat solutions). But this is some prime folk etymology in action. Because focus didn’t enter English this way. Instead, it came via some good historical science.

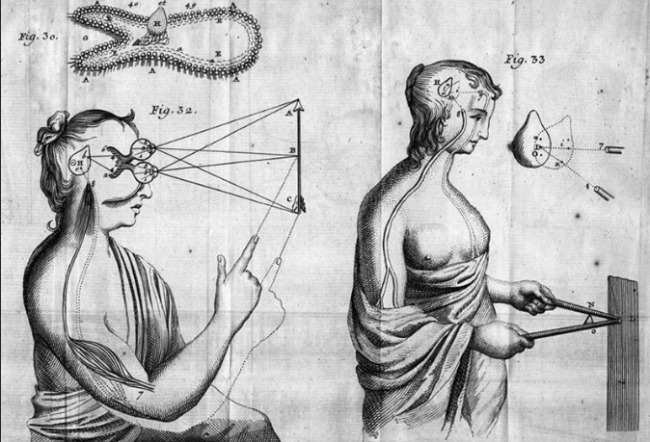

Johannes Kepler used the term ‘focus’ to refer to the mathematical point of convergence, in an analogy with the burning point on a lens (so the fire is there after all, just not quite how we might imagine it at first). This came in handy while he was busy inventing an improvement on the telescope that allowed for a much greater degree of magnification than Gallileo’s original design. Thomas Hobbes borrowed this meaning, and brought it into English in a mathematical context in 1656. Who knew Hobbes was into maths as well as depressing political philosophy? But of course, being a good 17th Century scholar he was actually into everything. Fascinated by mathematics and optics, he was mathematics tutor of the Prince of Wales between 1646 and 1648, and his disagreement with Robert Boyle over the validity of the experimental method forms the basis for one of the classic works within the History of Science, Leviathan and the Air Pump by Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer.

So in conclusion. ‘Focus’ is from telescopes via domestic hearths, Hobbes hated experiments but loved maths, and distraction is a frighteningly easy state to fall into. Right. Now that we’ve got that sorted, we can all get back to what we were meant to be doing ten minutes ago. Focus, people!

*although due to aforementioned distraction, the idea of thinking about any one thing for five whole minutes at a time seems, at this point, almost inconceivable.